This article is part of a series on technical debt. Check out the previous article:

Intro to evolutionary architecture

- Current architecture

- Problems with the current architecture

- Good architecture

- Evolutionary architecture

Evolutionary architecture refers to a software design approach that embraces change as a fundamental aspect of system development. Instead of aiming to create a fixed and perfect architecture upfront, it allows the system to evolve in response to new requirements, technologies, and insights. Evolutionary architecture is a critical tool for reducing technical debt.

Evolutionary design, or incremental design, is another term for this approach. Generally, evolutionary design refers to changes on a smaller scale, such as refactoring code or adding new features. On the other hand, evolutionary architecture refers to changes on a larger scale, such as reorganizing the codebase or splitting a monolithic application into microservices. That said, there is no strict boundary between the two terms. We will use the term evolutionary architecture.

In this article, we provide an example of scaling your codebase to accommodate a growing number of features and developers.

Current architecture

We base our example on a theoretical codebase, but real-world experiences inspire it. The problems and solutions we discuss are common in software development, especially in startups and small companies.

The initial state of our example codebase is a web application developed in a mono-repository. The application was built from the ground up with a simple architecture, focusing on adding new features and finding product-market fit.

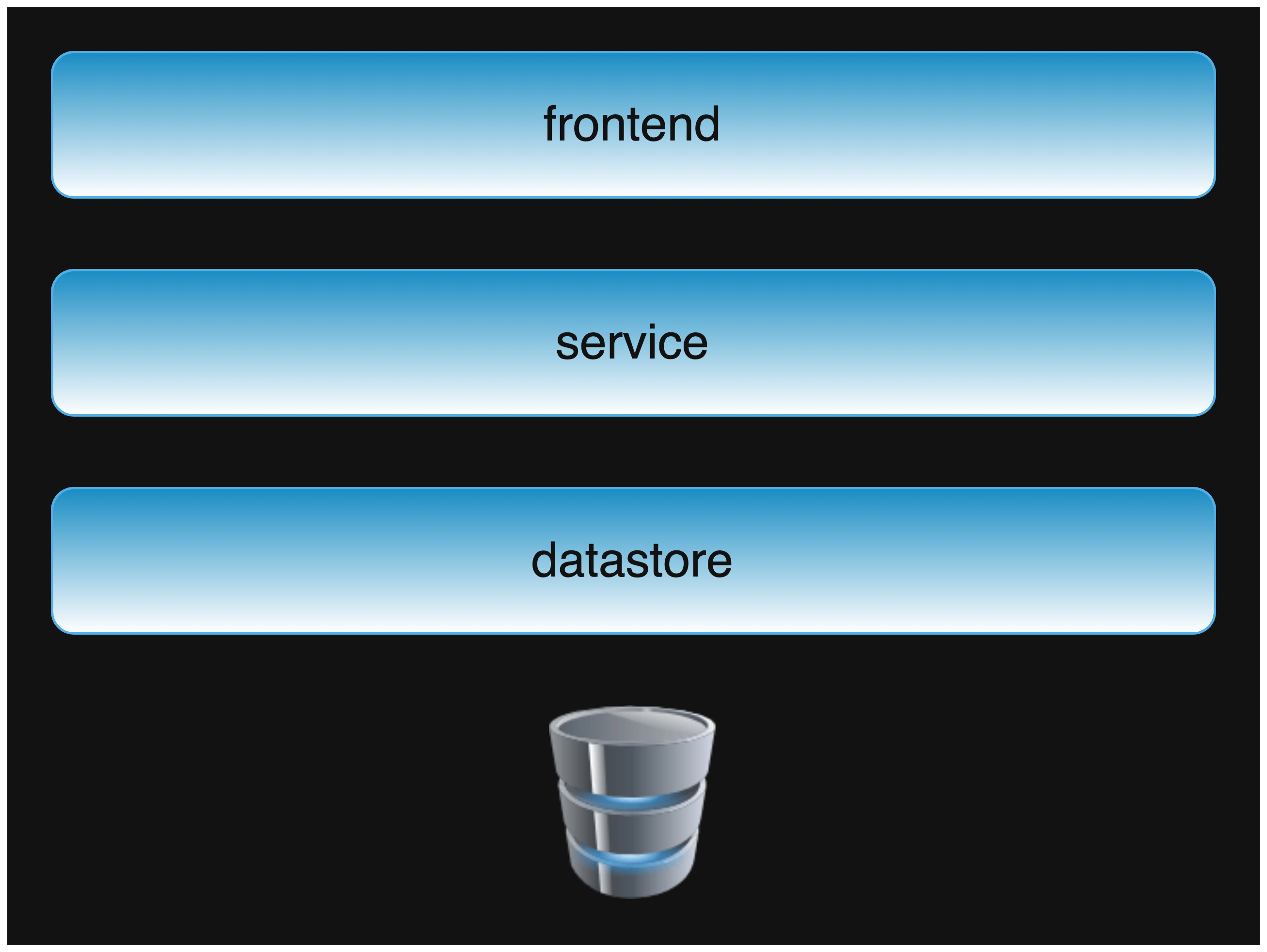

Current design with a few large modules.

The current design divides the codebase into a few large modules. We use the term module to mean a logical grouping of code in the same files and directories.

However, after a couple of years, the application has grown significantly in features, complexity, and team size. The organization now has three product teams working on different functional areas of the application. No one has updated the initial architecture, which is insufficient to support the growing codebase and development team.

Problems with the current architecture

A significant problem that the engineering team has been facing is an increase in bugs and a longer time to fix them. The code for each feature is sprinkled throughout the codebase and tightly coupled to other seemingly unrelated features. This complexity makes it difficult to understand, test, and keep existing features working as new ones are added.

Speaking of new features, the team has been struggling to add them on time. The codebase has become a tangled web of dependencies, and any change in one part of the codebase can have unintended consequences in other parts. Adding a feature requires modifying many parts of the codebase, which requires understanding the entire codebase, which many developers lack. The lack of knowledge and the changes to many parts of the codebase have led to features taking significantly longer to implement than initially estimated.

Maintaining feature branches for over a few days and making patch fixes to existing releases has become impossible. The codebase is so intertwined that any changes may cause merge conflicts. The increased likelihood of merge conflicts has discouraged developers from refactoring and cleaning up the code base. This tendency to leave the code as-is has perpetuated the slide in code quality.

Tests have also become a problem. The test suite has been in a frequent state of disrepair. There is no clear ownership of tests, so engineers have been reluctant to fix them. Some engineers have stopped paying attention to failing CI alerts, figuring that the problems are caused by one of the other two teams.

Tests have also become slower and slower, especially the integration tests that test the API and include the service layer, the datastore layer, and an actual database. These tests do not run in parallel; every additional feature slows down the compile and increases test time. Test files have become bloated with tests for multiple features, making them slow to load in the editor, difficult to navigate, and impossible to diff for PR reviews.

Finally, the onboarding time for new developers has been growing. It takes weeks for new developers to understand the codebase and start contributing.

Good architecture

At this point in the company’s life, an exemplary architecture would be separate groups of modules corresponding to the three product teams.

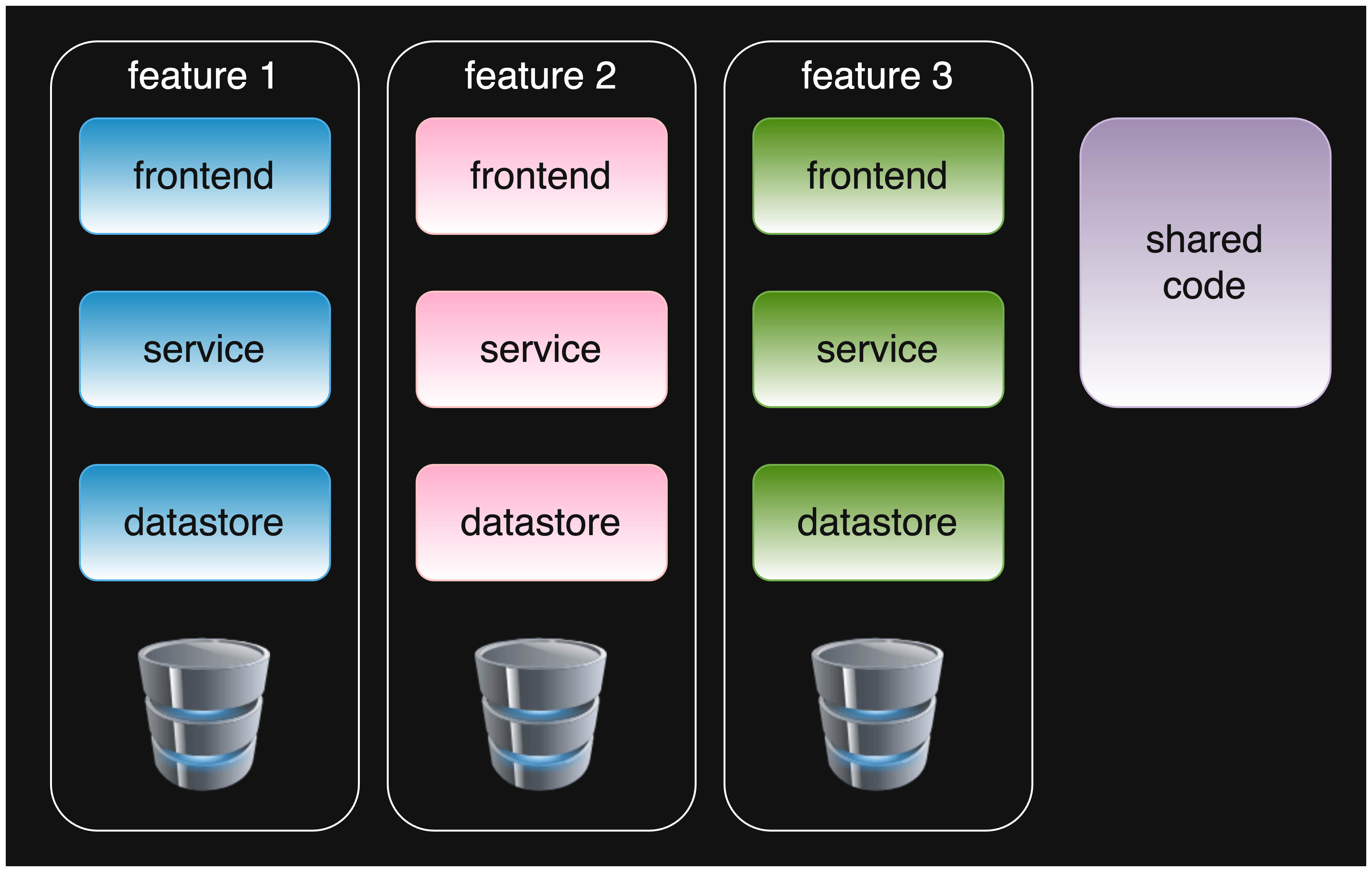

Good design with dedicated modules for each product team.

Each team would be responsible for its own set of modules, which aligns with Agile principles. The modules would be loosely coupled, and the teams would be able to work independently on their features without affecting other teams. The amount of code that each engineer has to understand and change would be drastically reduced.

This architecture would have eliminated or significantly reduced the problems that the engineering team has been facing.

- The reduced complexity and increased understanding of the codebase would lead to fewer and faster to fix bugs

- Faster feature development due to cleaner code and fewer dependencies

- Reduced merge conflicts for PRs, especially for database migrations and schema changes

- Rarely failing test suite due to clear ownership of tests

- Faster tests due to each team focusing on testing their slice of the product. Limited complete product integration tests would still be present.

- Faster onboarding time for new developers

However, the company does not have this architecture. Building this architecture upfront would have been foolish since it would have consumed critical engineering time. Yes, there was value in creating this structure upfront because it would have saved time in the long run, but this value was insufficient for a young company that may not be around in a few months.

Evolutionary architecture

Many companies and engineers find themselves in this situation. They have a codebase with poor architecture for today’s reality, blame the organization for not thinking about these problems earlier, and feel like they can’t improve the situation.

Evolutionary architecture is a way to incrementally improve the architecture of a codebase without having to do a big rewrite. It is a way to make the codebase better today than it was yesterday and better tomorrow than it is today.

This situation is not unique to this company. It is the norm. Most companies start with a simple architecture and codebase that is good enough for the first few features. As the company grows, the architecture becomes a bottleneck. Instead of worrying about not making the right decisions in the past, consider where the architecture needs to be a year or two from now and start moving towards that.

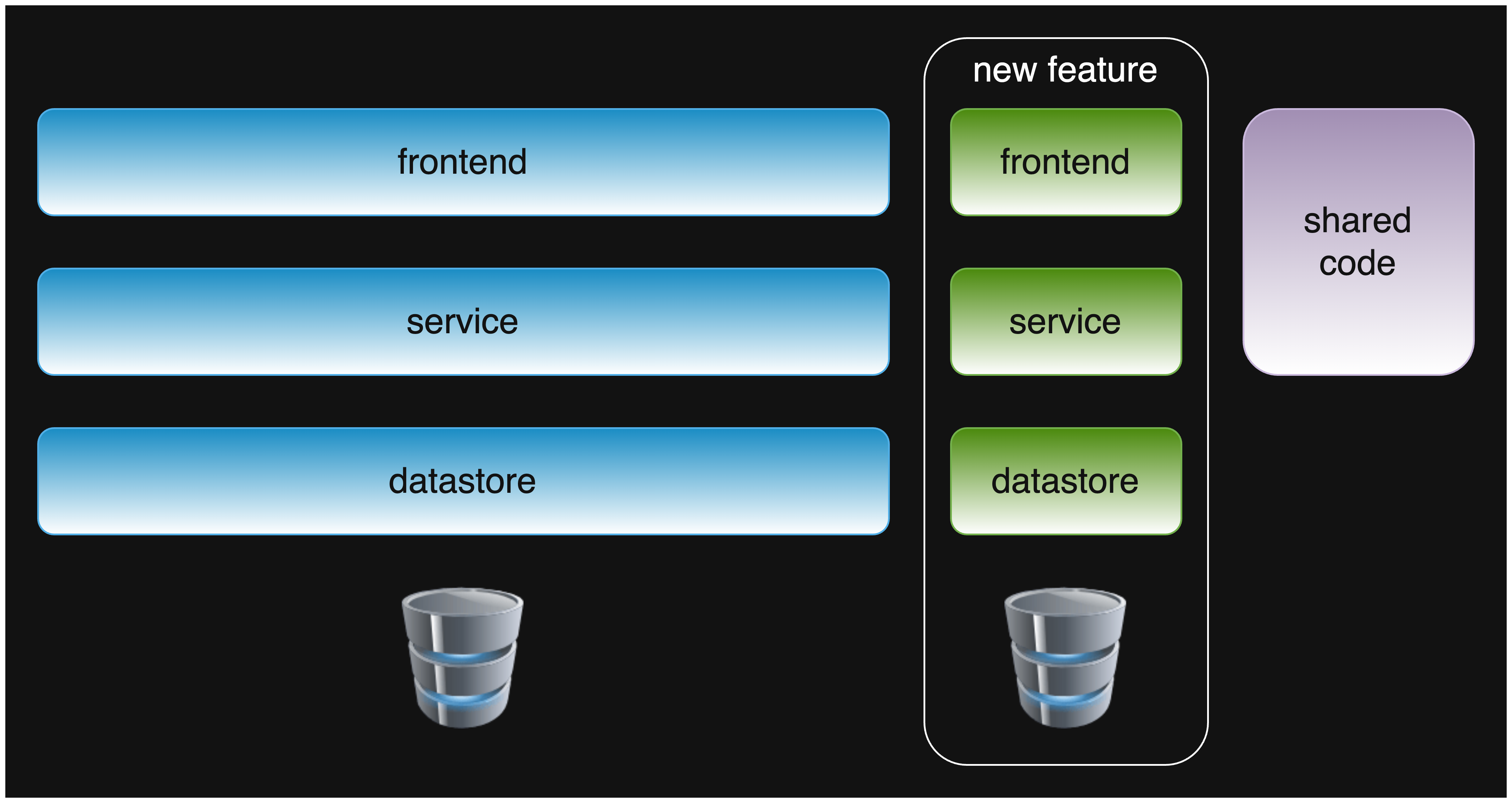

For example, when adding a new prominent feature to the product, decouple it from the rest of the codebase.

Evolutionary design with big features going into dedicated modules.

Our example shows all the modules decoupled, but it may be OK to decouple one or two.

Decoupling a feature from the rest of the codebase has many benefits similar to those we listed above for “good architecture.” Additional benefits include:

- Most of the feature can be tested by itself, reducing test time.

- The business gets the option to create a new team dedicated to the feature quickly – the code is already separate/independent

- Engineering can scale the feature separately from the rest of the product. For example, assign a dedicated database or split the feature into a microservice.

Code example of splitting the database schema

It is nice to read about a theoretical example, but seeing an actual code example is even better. In this code example, we begin with a monolithic application that has a single database schema. We then split the schema into two separate schemas. It is the starting point and a reference for decoupling a new feature from the rest of the codebase. Since this code example is a bit long and requires some context regarding the current implementation, we will not cover it in this article. Instead, jump to the code example section of the video below.

Link to the source code example decoupling a new backend feature from the rest of the codebase.

Track code complexity metrics

In the next article of this technical debt series, we go over the top code complexity metrics every software engineer should know.

Further reading

- The modular monolith that wasn’t

A real-world account of attempting to modularize a 500K-line codebase and the lessons learned.

And also

- Recently, we covered how to easily track engineering metrics.

- Previously, we demonstrated the most significant issues with GitHub’s code review process.

- We also showed how to create an architectural test that finds Go package dependencies.

- We also published an article on the common code refactorings to improve code readability.

- In addition, we summarized what every software engineer should know about AI.

- Lastly, we introduced the top Mermaid diagrams for software developers.

Watch how to scale your codebase with evolutionary architecture

Note: If you want to comment on this article, please do so on the YouTube video.